Originally Posted 8 November 2012

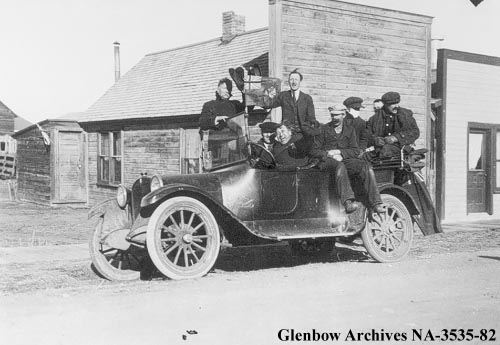

I’ve been struggling to figure out a way to incorporate more of my research into this blog, and with November 11th coming up I think I’ve found a way. While this doesn’t actually have much to do with my actual dissertation, I’ve combed through some of the digitized archival databases in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand to assemble some photographs from November 11th 1918. I didn’t have too much rhyme or reason for assembling these specific images, much of the selection was dictated by which databases gave permission to re-publish items from their collection, but I think they demonstrate how the Armistice was commemorated or celebrated across the three dominions of the British Empire. From larger centres like Sydney, Christchurch, or Vancouver, to small towns like Nanton, Alberta; Nannup, Western Australia; or Levin, Manawatu-Wanganui, photographs of the Armistice reveal the costumes and artefacts were used to mark the end of the Great War.

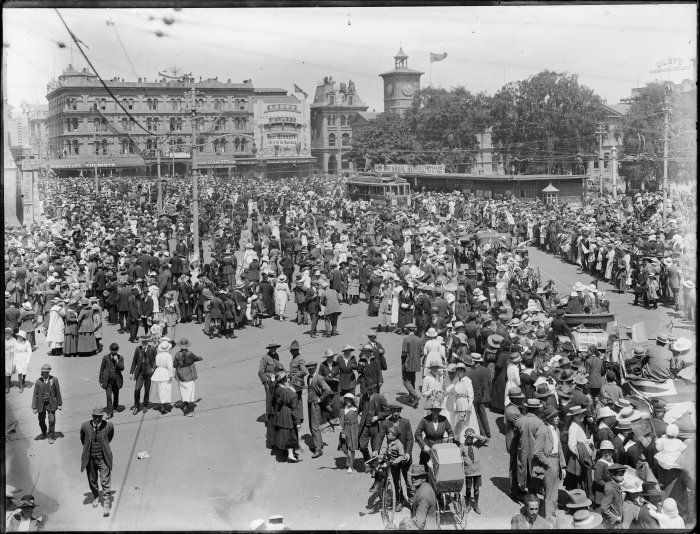

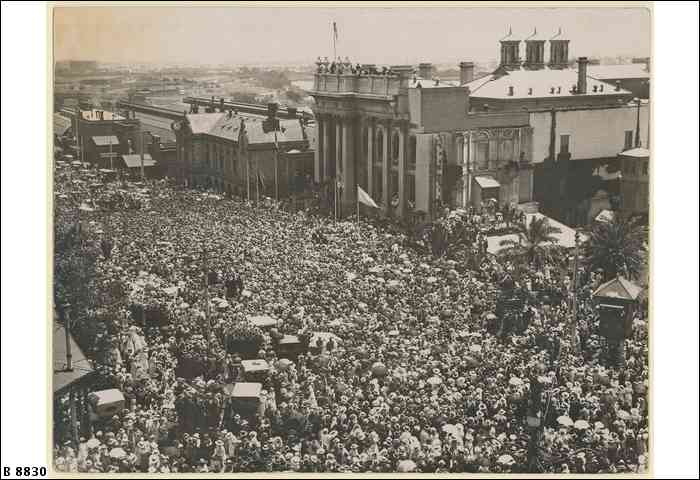

It’s interesting to see how giant props materialized for the Armistice celebrations. No doubt many of these were built for earlier recruiting or fundraising drives. In Sydney (below), a large mock-up of a battleship acted as a platform for speakers to address the massed crowds.

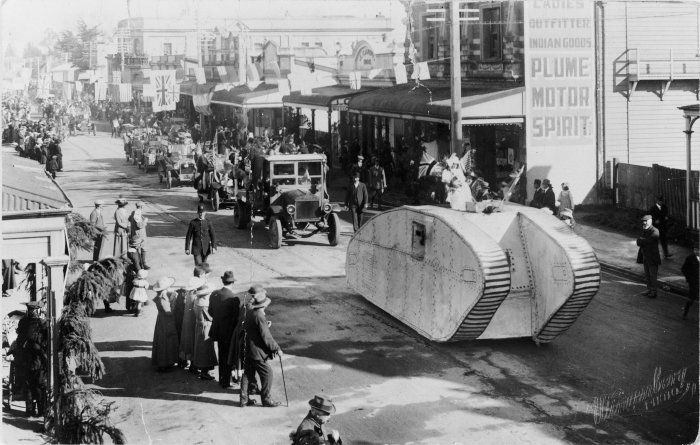

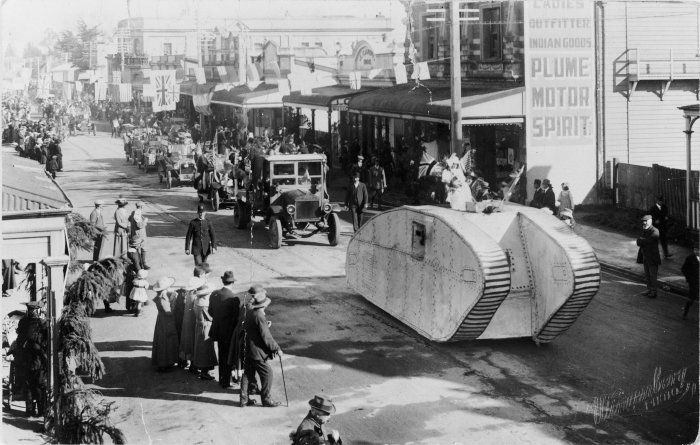

In Masterton, New Zealand, a mock-up of a tank rolls down the street as part of a parade. I suppose these huge replicas reflect how military hardware captured peoples’ attention on the home front, as they imagined the distant war.

I think it’s even more interesting to look at photos from smaller communities. Unlike the massive throngs of peoples in urban centres, small towns seemed a bit more coordinated in their celebrations. In Nannup, Western Australia, the community held a memorial service at its cenotaph, which had already been built before the conclusion of the war.

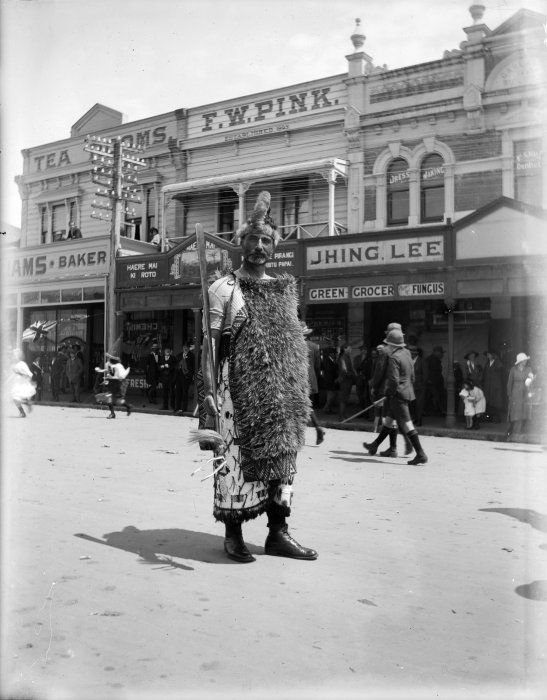

It’s also interesting to see how Indigenous peoples participated in the commemorations. It was easier to find photographs of Aboriginal Canadians or Maori taking part in Armistice celebrations. Both of these dominions actively recruited Indigenous soldiers, New Zealand more deliberately than Canada, but I was not able to find any pictures of Australian Aboriginals, which is not too surprising given Australia’s policies at the time. I also came across another picture of Canadian Aboriginals participating in a parade in Montreal, but the Archives de Montreal’s policies do not allow me to publish the image without their permission. These pictures reflect not only the participation of Indigenous peoples in the imperial war effort, but also the place of Indigenous peoples in the popular imagination of the dominions.

The Armistice celebrations in Levin, New Zealand made for an interesting set of photographs. While the one above shows a Maori in traditional dress, the remainder of the pictures from Levin show that the town celebrated with a large ‘fancy dress’ party.

It’s worth noting that the whole town celebrated in fancy dress, because the next picture shows that the Maori costume was not always worn with the utmost reverence or respect. While Indigenous peoples served in uniform and were present during Armistice celebrations in traditional dress, the image of a Pakeha in blackface aping a Maori dance serves as a reminder that Indigenous peoples remained very much in the margins of dominion society.

| Last in this series are pictures from the front lines. Even in the pictures of large crowds and parades, the images from France, Belgium, and the Middle East show a certain quiet disbelief which contrasts with the joy and jubilation of the home front. This contrast is probably the closest that this blog post will come to my dissertation research, but it is worth considering the reality of the war in Europe and comparing that to the way communities on the home front imagined the war.

|

The disparity between soldiers’ experiences of the war and the perception of the war on the home front is one of the pillars of my dissertation. Studies such as Leonard Smith’s Between Mutiny and Obedience or Gary Sheffield’s Leadership in the Trenches show how the combat experience or military culture kept soldiers fighting. Civilians on the home front were not subject to these pressures, and yet many contributed eagerly to support the war effort by volunteering their time and efforts. The enthusiasm with which many civilians essentially taxed themselves for the war effort raises questions about their perception of the war and the cause they were supporting. This is the phenomenon that I am studying in my dissertation.

The above images were collected from the following online archival databases:

The Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

The Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

The City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver.

The Glenbow Archives, Calgary.

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa.

The State Library of South Australia, Adelaide.

Reblogged this on Anzac Day 2015.